Generics In C#

Generics in C# were introduced into the C# language with version 2 of the C# specification and the goal was to allow us to reuse more code while still being typesafe.

The type parameters in c# generics allow you to create type-safe code without knowing the final type you will be working with. In many instances, you want the types to have certain characteristics, in which case you place constraints on the type. Also, C# methods can have generic type parameters as well whether or not the class itself does.

Generics in C# allows for code reuse, as generics can parameterize the types inside of a class, interface, method or delegate. It also helps to avoid nasty problems, like typecasting and boxing.

Contents

- Generics In C# With Example (The Linked List Data Structure Problem)

- C# Generic Class

- C# Generic Interface

- Generic Class And Method In C#

- IEnumerable Generic C#

- C# Generic Method

- C# Generic Delegate

- C# Generic Static Method

- C# Generic Constraints (C# Generic Where Keyword)

- Further Reading

Generics In C# With Example (The Linked List Data Structure Problem)

The below code is for a data structure known as a Linked List. Actually it’s a simple singly-linked list implementation, the Node type contains a reference to the next item in the list. This reference is used to allow iteration of the list.

The LinkedList class contains a single Node reference to the first item in the list known as root. Starting from that first node you can then step through the list by getting the next field. When next is null then you have reached the end of the list.

Now you don’t have to know the code for the linked list, it’s only going to be here to prove a point.

public class LinkedList

{

public class Node

{

// link to next Node in list

public Node next = null;

// value of this Node

public int data;

}

private Node root = null;

public Node First

{

get

{

return root;

}

}

public bool Any()

{

return root != null;

}

public void AddLast(int value)

{

Node n = new Node { data = value };

if (root == null)

{

root = n;

}

else

{

Node curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

curr = curr.next;

}

curr.next = n;

}

}

public void Remove(int data)

{

if (root != null && Object.Equals(root.data, data))

{

var node = root;

root = node.next;

node.next = null;

}

else

{

Node curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

if (curr.next != null && Object.Equals(curr.next.data, data))

{

var node = curr.next;

curr.next = node.next;

node.next = null;

break;

}

curr = curr.next;

}

}

}

}

Here’s my problem, it only stores int.

I cannot use it for bytes or strings or float or any other type of object, only int, because that’s the type of data I have. And the AddLast method only accepts int and the First property only returns Node object with data field of type int.

Now,

I want to use this linked list for different types of objects. I want to be able to store strings. How am I going to implement that? If you already know generics, pretend that you don’t, there are a couple of possible solutions. Let’s talk about them and see the pros and cons.

The Object Solution

One solution to my problem is to allow the linked list to work with objects instead of int. That is change the API, change the internal implementation, change everything to take object instead of int, because we are in C#, and everything we work with derives from System.Object.

public class LinkedListObject

{

public class Node

{

// link to next Node in list

public Node next = null;

// value of this Node

public object data;

}

private Node root = null;

public Node First

{

get

{

return root;

}

}

public bool Any()

{

return root != null;

}

public void AddLast(object value)

{

Node n = new Node { data = value };

if (root == null)

{

root = n;

}

else

{

Node curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

curr = curr.next;

}

curr.next = n;

}

}

public void Remove(object data)

{

if (root != null && Object.Equals(root.data, data))

{

var node = root;

root = node.next;

node.next = null;

}

else

{

Node curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

if (curr.next != null && Object.Equals(curr.next.data, data))

{

var node = curr.next;

curr.next = node.next;

node.next = null;

break;

}

curr = curr.next;

}

}

}

}

Let’s just check if the above changes are working below in the Main method that uses this linked list class. In this method, we will add four items and remove one item from the list. Eventually, it will contain three elements 1, 2, and 3.

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var list = new LinkedListObject();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.Remove(2);

while (list.Any())

{

var first = list.First;

list.Remove(first.data);

Console.WriteLine(first.data);

}

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

/*

Output:

1

2

3

*/

And this seems like we are off to a pretty good start, but there are two problems.

One will become very obvious when I try to do something interesting with a linked list, not just write out the contents, and the other problem is a hidden problem, that might cause my application to perform badly.

Let’s look at the first problem.

Here inside of the program, a Console mode application, essentially all I’m doing is passing some int values inside the linked list, and I just display all the content of the linked list of what’s inside.

If I really was working with a linked list of int, I’d probably want to do some math on the numbers. I’d want to average or sum a list of measurements. So let’s say instead of displaying the values out like this, I actually wanted to compute a sum of numbers that are inside the linked list.

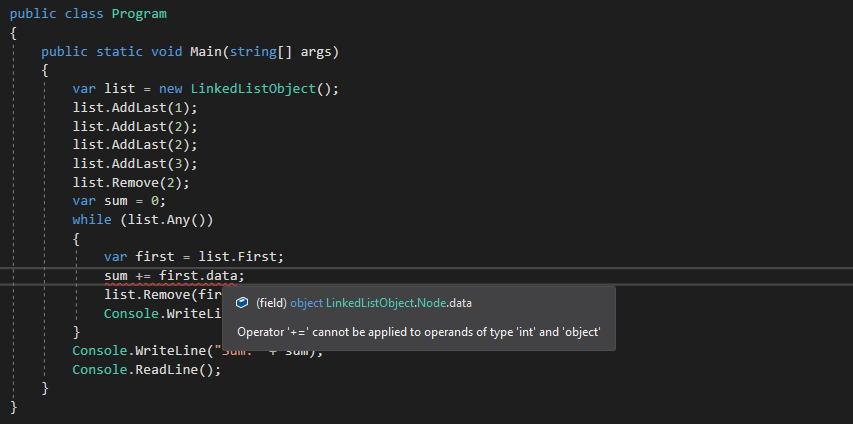

So I’ll say sum = 0, while list is not empty sum += first.data. But this starts to demonstrate one of the first problems. first.data field no longer returns an int, it returns an object reference.

To make that into an int, one thing I could do is a typecast. I could say yes I know it’s returning an object reference, but let’s just force it into being an int. And now add these things up for me and at the end here let me write out the sum that we compute.

But looking at this now it’s not as nice as it could be because if first.data actually returned an int instead of an object reference, I wouldn’t need this cast and the code would be a little bit easier to read.

Also,

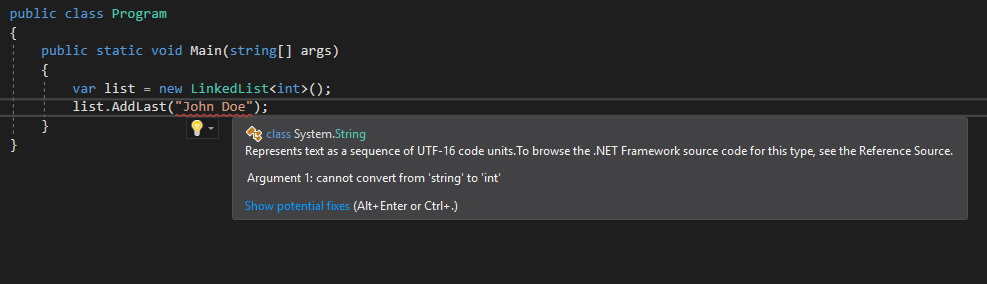

I’m also not guaranteed to get an int since the AddLast method accepts just about anything, it takes an object reference. Someone could say list.AddLast("John Doe"), and just put in a string. And that means when the application runs, it’s going to explode with an invalid cast exception, because I just tried to take a string and cast it into an int.

So yes, my linked list does work with int, and float, and any other type of object, but it’s no longer typesafe.

It’s not as easy to work with. What I’ll have to do now is more than just a typecast, I’m going to have to do some sort of check to make sure that that actually is an int. So I could add a try-catch block around the casting.

Let me show you this try-catch version of the program, which is good. But I have to write a little more code, so it’s not as nice to work with.

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var list = new LinkedListObject();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.AddLast("John Doe");

list.Remove(2);

var sum = 0;

while (list.Any())

{

var first = list.First;

try

{

sum += (int)first.data;

}

catch (Exception)

{ }

list.Remove(first.data);

Console.WriteLine(first.data);

}

Console.WriteLine("Sum:"+ sum);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

/*

1

2

3

John Doe

Sum:6

*/

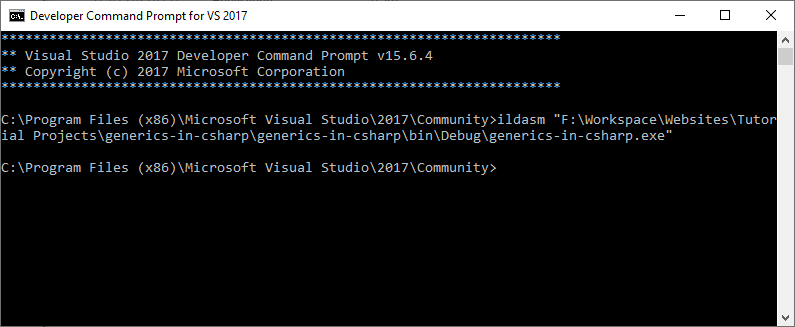

There’s also the hidden problem that I alluded to. Let me go to the command prompt for Visual Studio and open up a tool that’s always installed with Visual Studio, it’s called ILDASM. That’s short for Intermediate Language Disassembler and with this tool I can browse to any EXE or DLL, any type of assembly compiled for. NET.

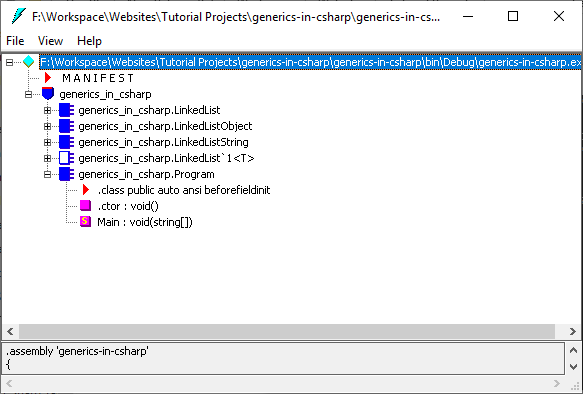

So my program will currently be in folder generics-in-csharp > bin > Debug, I’ll open up file generics-in-csharp.exe in ILDASM.

And one of the many things that ILDASM will show me, if I dig around inside of here, will be the intermediate language instructions in the assembly.

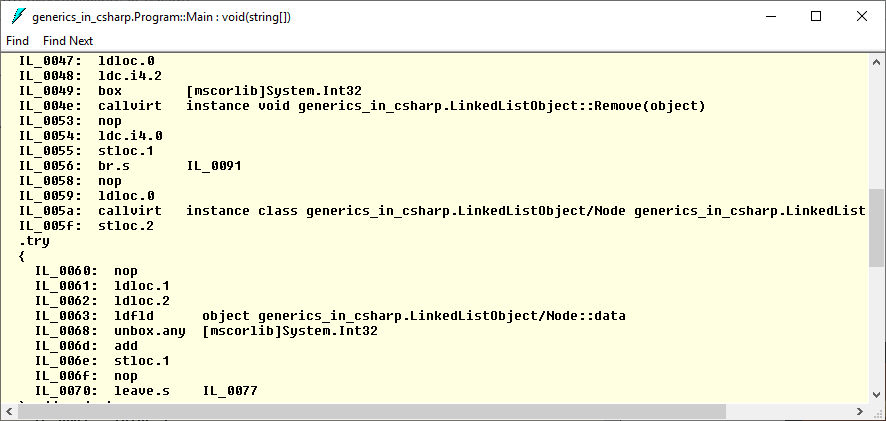

These are the OpCodes, the instructions for the virtual machine that the common language runtime provides, and here inside of the main method of the application, I can see there is a line of code that is boxing an int32.

If you’re not familiar with the boxing operation, here is the short version of the story is that when we take a value type like int, longs, int, dates, and try to interact with it through an object reference, the C# compiler is forced to take the value, allocate space on the heap, and copy that value to the heap.

But boxing operations are not inherently bad. The problem is most people using a Linked List like this will have a large list of items, it can be 10,000 or 100,000 items.

And when you start boxing large amounts of data like that, a large number of items, then you can run into performance issues, because it takes additional time to allocate the memory, copy the value to the heap, and then eventually you’ll want to work with the data. And that’s going to require an unboxing operation, taking that value off the heap and making it a double that I can sum again. So all in all, we would like to avoid boxing if we could, if there’s an easier way to do it.

So let’s forget about this approach of using objects inside of the LinkedList. We don’t necessarily want the object data, we don’t want AddLast to take an object, we don’t want Node.data field to be an object, that would fix two of the problems we’ve seen in this clip. We want strong typing, we want to only store strings or int or one type of object in each LinkedList, and we want to avoid boxing value types. So, let’s try another approach.

Copy and Paste Solution

Now, I’ll take the LinkedList class that I have, copy it, and then I’m just going to paste it here inside of the same file. And now I’ll change the name of this class, let me call it LinkedListString. And now I just need to make it work with string, so I want data in the Node to be a string. I want the AddLast method to take only strings, I want the First.data to be a string, and voila! I now have a LinkedList that works with strings. Below is an example

public class LinkedListString

{

public class Node

{

// link to next Node in list

public Node next = null;

// value of this Node

public string data;

}

private Node root = null;

public Node First

{

get

{

return root;

}

}

public bool Any()

{

return root != null;

}

public void AddLast(string value)

{

Node n = new Node { data = value };

if (root == null)

{

root = n;

}

else

{

Node curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

curr = curr.next;

}

curr.next = n;

}

}

public void Remove(string data)

{

if (root != null && Object.Equals(root.data, data))

{

var node = root;

root = node.next;

node.next = null;

}

else

{

Node curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

if (curr.next != null && Object.Equals(curr.next.data, data))

{

var node = curr.next;

curr.next = node.next;

node.next = null;

break;

}

curr = curr.next;

}

}

}

}

But, I just remembered I also need one that works with floats too. Well fortunately with today’s powerful computers, I can copy/paste as many classes as I need.

Except,

Copy/paste is like a bad idea. What I really want to do is keep all my logic for managing a LinkedList at one place, and I want to reuse that same logic to manage a list for int, for strings, for custom objects, just everything.

And if you remember what I did here was paste in some new code. And essentially I needed to go through the new class and just change the main type of that class, search and replace the word int, and replace it with string, and that is exactly what generics can do for me.

Generics can allow me to parameterize my data type so I don’t have to commit to a specific type here at compile time like string or double, instead I’ll have a placeholder. I’m going to call it T for type and I’ll figure out the actual type sometime later after compilation. Let’s take a step back and look at this concept.

C# Generic Class

Generics were introduced into the C# language with version 2 of the C# specification and the goal was to allow us to reuse more code while still being typesafe.

Like our LinkedList class, we’ve discussed before, we want to reuse the code inside the class, but still be able to create LinkedList that can work with specific types, like strings or int or our domain objects like customer objects.

The way this works is that we’ll have a placeholder for types inside our code and the client, that is the code using our class, gets to pick a type when they instantiate an instance of our class.

var list1 = new LinkedList<string>();

var list2 = new LinkedList<int>();

So I can instantiate one LinkedList object that can only store integers, and another LinkedList object that can only store strings, and these will both be typesafe.

Also, I wouldn’t be able to add a string to the LinkedList of integers as that would be a compiler error.

Steps To Create Generic Class In C#

Here are the steps to create a generic class:

-

Syntactically the way this is done is to add a generic type parameter to the class. The parameter goes inside of angle brackets and you can have more than one type parameter.

-

It is quite common for a single type parameter to be called

<T>, T for type, and think of this as a parameter for your class definition. -

The T can parameterize the types that you use inside, so instead of creating a

Nodeclass, I can create aNode<T>class, where T is the type parameter passed to my class. Similarly, instead ofLinkedListclass I will createLinkedList<T>. The way I would read the name of the class now is LinkedList of T.

Let’s take a look at this in our code and see how to use it.

public class LinkedList<T>

{

public class Node<T>

{

// link to next Node in list

public Node<T> next = null;

// value of this Node

public T data;

}

private Node<T> root = null;

public Node<T> First

{

get

{

return root;

}

}

public bool Any()

{

return root != null;

}

public void AddLast(T value)

{

Node<T> n = new Node<T> { data = value };

if (root == null)

{

root = n;

}

else

{

Node<T> curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

curr = curr.next;

}

curr.next = n;

}

}

public void Remove(T data)

{

if (root != null && Object.Equals(root.data, data))

{

var node = root;

root = node.next;

node.next = null;

}

else

{

Node<T> curr = root;

while (curr.next != null)

{

if (curr.next != null && Object.Equals(curr.next.data, data))

{

var node = curr.next;

curr.next = node.next;

node.next = null;

break;

}

curr = curr.next;

}

}

}

}

Our final Main method will look like this,

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var list = new LinkedList<int>();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.Remove(2);

var sum = 0;

while (list.Any())

{

var first = list.First;

sum += first.data;

list.Remove(first.data);

Console.WriteLine(first.data);

}

Console.WriteLine("Sum:" + sum);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

Generics are very popular for collections and data structures like linked lists, dictionaries and so forth, because the real code inside these data structures is code to manage the data structure itself. It doesn’t really care what type of objects you’re storing inside, the code just needs to manage its internal state, its internal pointers, and it lets you read and write data, strongly-typed data, and it does that without any performance penalties like boxing.

So, Generics allow for code reuse, because generic arguments can parameterize the types inside of a class and code reuse is good. We can reuse code and avoid nasty problems, like typecasting and boxing.

Note: You can also use generic classes that have already been written; .NET Framework has generic collection classes of List, LinkedList, Stack, Queue, and BitArray, these are important in everyday programming and knowing all about the data structures will help you write efficient code.

C# Generic Interface

Similar to generic classes are generic interfaces, you can define a parameter T on the interface level, and your methods can use this parameter in their prototype, so any class that will be implementing this interface will naturally implement the parameter T within its own methods. You can also add constraints to generic interfaces. Note that the class which will be implementing the generic interface must define the parameter T. Here is an example, inspired by our LinkedList class,

public interface ILinkedList<T>

{

LinkedList<T>.Node<T> First { get; }

void AddLast(T value);

bool Any();

void Remove(T data);

}

Above we have an interface for LinkedList containing all the properties and methods require for defining the contract a LinkedList must implement. Now, all we have to do is inherit our LinkedList<T> with ILinkedList<T> and implement the logic which we already did in the above examples.

public class LinkedList<T> : ILinkedList<T>

{

...

}

So now in our final program, we can use or ILinkedList<T> as list type and thus can replace our implementation of the list with any class that implements our ILinkedList<T>

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

ILinkedList<int> list = new LinkedList<int>();

...

}

}

Generic Class And Method In C#

Let’s discuss some rules of generics that will help you understand how to use interfaces and classes with generics.

More Than One Type Parameter

A class or an interface can define more than one type parameter, as follows:

class Dictionary<K, V>

{

...

}

interface IDictionary<K, V>

{

...

}

Closed Constructed Type

Classes can extend closed constructed generic classes, as follows:

class BaseClass<T> { }

class SampleClass : BaseClass<string> { }

same goes for generic interfaces:

interface IBaseInterface<T> { }

interface ISampleInterface : IBaseInterface<string> { }

class SampleClass : IBaseInterface<string> { }

Partial Closed Constructed Types

Generic classes can extend other generic classes or closed constructed classes as long as the class parameter list supplies all arguments required by the base generic class, as follows:

class BaseClass<T, U> { }

class SampleClass<T> : BaseClass<T, string> { } //No error

Similarly, Generic interfaces/classes can implement other generic interfaces or closed constructed interfaces as long as the interface/class parameter list supplies all arguments required by the base interface, as follows:

class IBaseInterface<T, U> { }

class SampleClass<T> : IBaseInterface<T, string> { } //No error

class ISampleInterface<T> : IBaseInterface<T, string> { } //No error

It is often useful to define interfaces either for generic collection classes, or for the generic classes that represent items in the collection.

The .NET Framework class library defines several generic interfaces for use with the collection classes in the System.Collections.Generic namespace. Let’s have a look on one such .NET interface.

IEnumerable Generic C#

The IEnumerable and IEnumerator interface in .NET helps you to implement the iterator pattern, which enables you to access all elements in a collection without caring about how it’s exactly implemented.

You can find these interfaces in the System.Collection and System.Collections.

Generic namespaces. When using the iterator pattern, you can just as easily iterate over the

elements in an array, a list, or a custom collection.

It is heavily used in LINQ, which can generically access all kinds of collections without actually caring about the type of collection.

The foreach statement in C# is some nice syntactic sugar that hides from you that you are using the GetEnumerator and MoveNext methods. Below example shows how to iterate over a collection without using foreach.

Syntactic sugar of the foreach statement

List<int> numbers = new List<int> { 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9 };

using (List<int>.Enumerator enumerator = numbers.GetEnumerator())

{

while (enumerator.MoveNext()) Console.WriteLine(enumerator.Current);

}

The GetEnumerator function on an IEnumerable returns an IEnumerator. You can think of this in the way it’s used on a database: IEnumerable

The enumerator has a MoveNext method that returns the next item in the collection. You can have multiple database cursors around that all keep track of their state.

Before C# 2 implementing IEnumerable on your own types was quite a hassle. You need to keep track of the current state and implement other functionality such as checking whether the collection was modified while you were enumerating over it. C# 2 made this a lot easier, let’s implement this iterator pattern in our generic LinkedList class.

Now,

There are two ways we can implement IEnumerable<T> , one way is to inherit IEnumerable<T> in ILinkedList<T> interface or implement it directly at LinkedList<T> class, like this:

public class LinkedList<T> : ILinkedList<T>, IEnumerable<T>

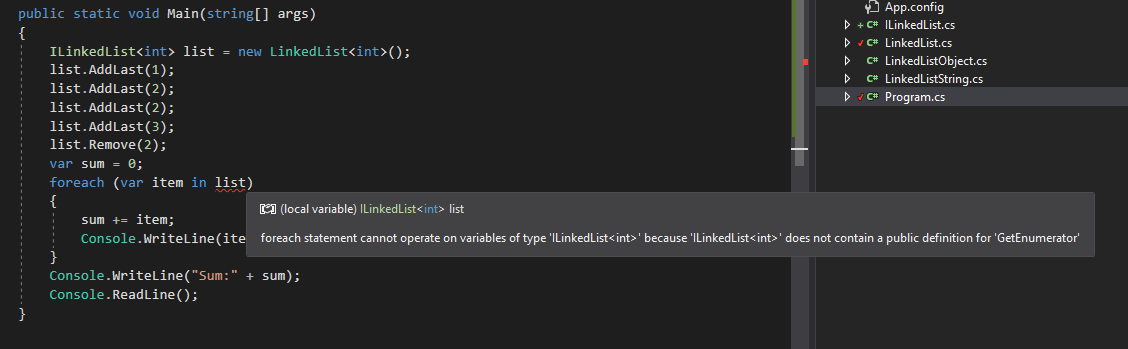

If we implement directly in our LinkedList class that will create problem while iterating on ILinkedList type like this:

So, instead we will inherit it on ILinkedList interface and implement the required methods in LinkedList class:

public interface ILinkedList<T> : IEnumerable<T>

{

LinkedList<T>.Node<T> First { get; }

void AddLast(T value);

bool Any();

void Remove(T data);

}

using System;

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

public class LinkedList<T> : ILinkedList<T>

{

public class Node<T>

{

// link to next Node in list

public Node<T> next = null;

// value of this Node

public T data;

}

...

...

//below is the require implementation for IEnumerable<T>

public IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator()

{

Node<T> curr = root;

while (curr != null)

{

yield return curr.data;

curr = curr.next;

}

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

Notice the yield return in the GetEnumerator function. Yield is a special keyword that can be used only in the context of iterators. It instructs the compiler to convert this regular code to a state machine. The generated code keeps track of where you are in the collection and it implements methods such as MoveNext and Current.

Because creating iterators is so easy now, it has suddenly become a feature that you can use in your code quite easily. Whenever you do a lot of manual loops through the same data structure, think about the iterator pattern and how it can help you create way nicer code.

Let’s see how this improves our code readability in our final program,

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

ILinkedList<int> list = new LinkedList<int>();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.Remove(2);

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in list)

{

sum += item;

Console.WriteLine(item);

}

Console.WriteLine("Sum:" + sum);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

C# Generic Method

Let’s see a very new type of problem, now, for instance if we have a LinkedList<double>, someone wants to scan through the LinkedList<double> and look at each item as an integer to do some special calculation after the double value is rounded, and someone else wants to convert the double to a string to send the contents to a diagnostic logger that only accepts string types. So, the question is how can we pull this off?

Well, first let’s take the simple case of converting whatever is inside the LinkedList to a 32-bit integer. And for the simple case of always converting to an integer, I might consider creating a method AsEnumerableOfInt, which will be a method that returns IEnumerableOfInt so that each item inside comes back as an integer value.

public IEnumerable<int> AsEnumerableOfInt()

{

...

}

But what about strings? In that case, perhaps I could also have AsEnumerableOfString that returns IEnumerableOfString. But once again we’re facing a scenario where we are writing code and only the type name changes. And as we saw with generic classes, it’s valuable to be able to parameterize code using type parameters so we only need to write the code once. We want to do that when we’re duplicating code and only the type name changes. And fortunately, type parameters can also be applied to methods.

So, I want to write this API using type parameters, and when I do that, I’m only going to have one AsEnumerableOf method. I can do that by using angle brackets, but this time the brackets are after the method name, not the class name, and the first question will be what do I want to name this type parameter? I don’t want to call it T because T is already a type parameter that is in effect throughout this class definition, and when someone constructs a LinkedList<double>, T is already a double, presumably though one to convert double to some other type like int, so I don’t want to reuse T here.

I want a new type parameter, one that is available just to this method. So, let me call it TOutput. When you invoke this method, you have to tell me the type of output that you’re expecting. And now TOutput becomes a generic type parameter that is available throughout this method.

public IEnumerable<TOutput> AsEnumerableOf<TOutput>()

{

...

}

Note: When I implement a generic method parameter, I can use it anywhere in the method definition. I can use it inside the method. I can also use it in the return type for this method, but I wouldn’t be able to use it outside that method.

And now I have a generic class with a generic method. A generic method doesn’t have to be part of a generic type. I could have that method on a non-generic type, and we’ll see examples of that later. The next question is how do I implement a method like this?

I want a method, a public method, called AsEnumerableOf

Well,

Fortunately .NET has a class that I can use to get a converter that knows how to convert quite a few different types. If I go to the TypeDescriptor class, and TypeDescriptor is in the System.ComponentModelnamespace, if I go up to that class, there is a static method there, GetConverter. And GetConverter doesn’t know how to do all different types of conversions, but it knows how to do quite a few, particularly among primitive types like ints and doubles and strings.

public IEnumerable<TOutput> AsEnumerableOf<TOutput>()

{

var converter = TypeDescriptor.GetConverter(...);

...

}

But,

I have to give GetConverter a parameter. One of the method overloads here takes a type, and what I’m going to ask TypeDescriptor. GetConverter to do is to give me a converter for the type T. If that’s double, I want something that knows how to convert double to other things. If T is an int, I want to get a converter that will convert ints to different things, and I can do that by passing T, the type. And it turns out the typeof operator will work just fine against generic type parameters.

public IEnumerable<TOutput> AsEnumerableOf<TOutput>()

{

var converter = TypeDescriptor.GetConverter(typeof(T));

...

}

So,

If this is a LinkedList<double>, I’ve just asked to get the converter for typeof double. And once I have a converter, I could use that on each item in the LinkedList. So, let’s create a loop. for the item in our list, I’ll get the converter to convert to this destination type. I have to pass in the value that is the thing I want to covert, that’s my item, and now I need the destination type.

So, am I trying to convert a double to an int or a double to a string? I’m not sure at compile time. All I know is that I have TOutput that represents the type that I want to convert to. So, once again, I could use the typeof operator and say please convert that item to typeof TOutput, and then I could return that result. I’ll use yield return to build an IEnumerable and return that result.

public IEnumerable<TOutput> AsEnumerableOf<TOutput>()

{

var converter = TypeDescriptor.GetConverter(typeof(T));

foreach (var item in this)

{

yield return (TOutput)converter.ConvertTo(item, typeof(TOutput));

}

}

And let’s try it out.

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var list = new LinkedList<double>();

list.AddLast(1.5);

list.AddLast(2.2);

list.AddLast(2.6);

list.AddLast(3.3);

list.Remove(2.2);

var sum = 0D;

foreach (var item in list.AsEnumerableOf<int>())

{

sum += item;

Console.WriteLine(item);

}

Console.WriteLine("Sum:"+ sum);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

In the above program, I have a LinkedList<double>. Here we have to be explicit and say I want the LinkedList as AsEnumerableOf<int>. So, T for LinkedList will be type double, TOutput for the AsEnumerableOf method will be type int, and I should be able to loop through all the items in asInts and be able to see integer values come out.

C# Generic Delegate

Closely related to methods and generic methods in. NET are delegates and generic delegates because a delegate, it’s a type that I can use to define variables that point to other methods.

Delegate is a type that essentially describes a method signature with its return type, so I can create variables that point to other methods and invoke those methods indirectly through my variable and do so in a type-safe way.

Before moving forward I want to point out some changes I have made in my Main method,

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

LinkedList<int> list = GenerateData();

Display(list);

Console.ReadLine();

}

private static LinkedList<int> GenerateData()

{

var list = new LinkedList<int>();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.Remove(2);

return list;

}

private static void Display(LinkedList<int> list)

{

foreach (var item in list)

{

Console.WriteLine(item);

}

}

}

As you can see from the above code I have created two separate methods, one for creating LinkedList of int, and the second one for displaying data within it. This gives me some readability and separation of concern to some extent.

Now,

Let’s imagine that inside of Display method I don’t feel comfortable using Console.WriteLine directly. Instead, I want Display to just be responsible for iterating properly through the LinkedList, picking out each item, and then using some layer of indirection to actually print the item. Where does print come from?

Well, I could have someone from the outside pass me in a variable printer, and I’ll use that variable as a method by applying parentheses to it, invoking it, passing in an item. The question is what type is a printer?

Well, because I want to use the printer like a method, the printer will have to be a delegate.

Let me create a delegate, a public delegate using the delegate keyword. And when you define a custom delegate like this, you’re essentially defining the type of method that you want to be able to reach through this delegate.

We will define a method that doesn’t have a return type. So, the return is void. And then the name of my delegate will be Printer. Also, we will need to take a parameter. Below is the code for the same.

delegate void Printer(object data);

This method has to take an object reference, and we’ll call the parameter data. And now I have a new type, a type called Printer.

I can define parameters and variables of that type, so let me take a printer variable of type Printer in Display method,

private static void Display(LinkedList<int> list, Printer printer)

{

foreach (var item in list)

{

printer(item);

}

}

So,

Now, I have a layer of indirection between Display and the ultimate output. When it calls printer(item), it doesn’t know if it’s writing to the screen or a file or a database. All it needs to do is iterate through the items correctly and call print for each one.

So, back in the program when I invoke Display, I now need to give it a delegate parameter. So, I will initialize a new Printer object and will point it to Console.WriteLine, and then I have something that I can pass to Display.

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

LinkedList<int> list = GenerateData();

Display(list, new Printer(Console.WriteLine));

Console.ReadLine();

}

And if I do a build at this point, the C# compiler is perfectly happy. I’ve created a Printer, initialized it, it’ll point to a method, ConsoleWrite, passing that into the Display method, which will use it.

public class Program

{

delegate void Printer(object data);

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

LinkedList<int> list = GenerateData();

Display(list, new Printer(Console.WriteLine));

Console.ReadLine();

}

private static LinkedList<int> GenerateData()

{

var list = new LinkedList<int>();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.Remove(2);

return list;

}

private static void Display(LinkedList<int> list, Printer printer)

{

foreach (var item in list)

{

printer(item);

}

}

}

So, if we run the program what we should see is that I can still Display out and printed to the screen correctly.

Now, of course, when Display goes to invoke print with an int value, since print takes an object reference, we’ll once again be in a situation where some boxing occurs. How could I avoid this boxing? Well, I could do it by strongly typing the Printer delegate using generics.

So, just like we can have generic classes and generic methods, delegates too can have generic type parameters.

So, I want a Printer

delegate void Printer<T>(T data);

And now for the Display method, I will have a Printer

public class Program

{

delegate void Printer<T>(T data);

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

LinkedList<int> list = GenerateData();

Display(list, new Printer<int>(Console.WriteLine));

Console.ReadLine();

}

private static LinkedList<int> GenerateData()

{

var list = new LinkedList<int>();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.Remove(2);

return list;

}

private static void Display(LinkedList<int> list, Printer<int> printer)

{

foreach (var item in list)

{

printer(item);

}

}

}

and you can see that this code is perfectly happy.

And now if I run this program, there shouldn’t be any visible difference in the way this behaves, but we are now using a strongly typed delegate. That will help me prevent boxing, and ultimately delegate types are extremely useful in. NET.

C# Generic Static Method

You can also further simplify the Display method using extension method and generic method. Below is the code for the same.

namespace generics_in_csharp

{

public delegate void Printer<T>(T data);

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

LinkedList<int> list = GenerateData();

list.Display(Console.WriteLine);

Console.ReadLine();

}

private static LinkedList<int> GenerateData()

{

var list = new LinkedList<int>();

list.AddLast(1);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(2);

list.AddLast(3);

list.Remove(2);

return list;

}

}

public static class Extension

{

public static void Display<T>(this LinkedList<T> list, Printer<T> printer)

{

foreach (var item in list)

{

printer(item);

}

}

}

}

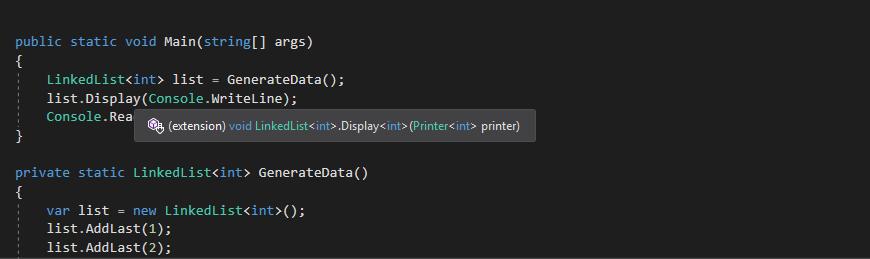

From the above image, you can see that the C# compiler is smart enough to understand the Type of T based on the parameter used.

With delegate types, I have a way to invoke methods through a layer of indirection, through some sort of variable that could point to different methods. And this is so useful that several delegate types are already built into. NET. There are enough delegate types around that I don’t need to define my custom delegate here called Printer.

Inside of. NET, there are three general-purpose delegate types. These are Func, Action, and Predicate. These Action, Func, and Predicate delegate types extremely useful. In fact, all of the LINQ operators take Funcs of different types.

So, if you’re using where, order by, select, join, group by, all of those wonderful LINQ operators that operate on IEnumerable

C# Generic Constraints (C# Generic Where Keyword)

Constraints (basically restriction about the parameterized type) can be added to generics with the help of the where keyword.

Constraints could mean that the parameterized type has to be a reference type or that it has to derive from a specific class for example. These constraints avoid compile-time errors. For more information about them, check out the Constraints on type parameters (C# Programming Guide).

It lists 6 different types of constraints:

| Constraint | Description |

|---|---|

| where T : struct | The type argument must be a value type. Any value type except Nullable can be specified. |

| where T : class | The type argument must be a reference type; this applies also to any class, interface, delegate, or array type. |

| where T : new() | The type argument must have a public parameterless constructor. When used together with other constraints, the new() constraint must be specified last. |

| where T : <base class name> | The type argument must be or derive from the specified base class. |

| where T : <interface name> | The type argument must be or implement the specified interface. Multiple interface constraints can be specified. The constraining interface can also be generic. |

| where T : U | The type argument supplied for T must be or derive from the argument supplied for U. |

The example below shows a generic class declaration where the parameterized type has to implement a specific interface.

interface ICustomInterface

{ }

public class Class2 : ICustomInterface

public class CustomList<T> where T : ICustomInterface

{

void AddToList(T element)

{}

}

public class Class1

{

public Class1()

{

CustomList<string> myCustomList1 = new CustomList<string>(); //Error

CustomList<Class2> myCustomList1 = new CustomList<Class2>(); //No Error

}

}

We will get an error with types that don’t implement ICustomInterface, like the type string here.

Also, multiple interfaces can be specified as constraints on a single type, as follows:

class LinkedList<T> where T : System.IComparable<T>, IEnumerable<T>

{

...

}

Further Reading

-

Generic Collections in .NET - Microsoft Docs - You can also use generic classes that have already been written; .NET Framework has generic collection classes of List, LinkedList, Stack, Queue, and BitArray, these are important in everyday programming and knowing all about the data structures will help you write efficient code.

-

Pitfalls of C# Generics and Their Solution Using Concepts by Julia Belyakova and Stanislav Mikhalkovich - Main pitfalls of C# generics are considered in this research paper. Extending C# language with concepts which can be simultaneously used with interfaces is proposed to solve the problems of generics; a design and translation of concepts are outlined.

-

Generic Repository Pattern C# - Creating a repository class for each entity type could result in a lot of repetitive code. Generic repository pattern is a way to minimize this repetition and have single base repository work for all type of data.

comments powered by Disqus